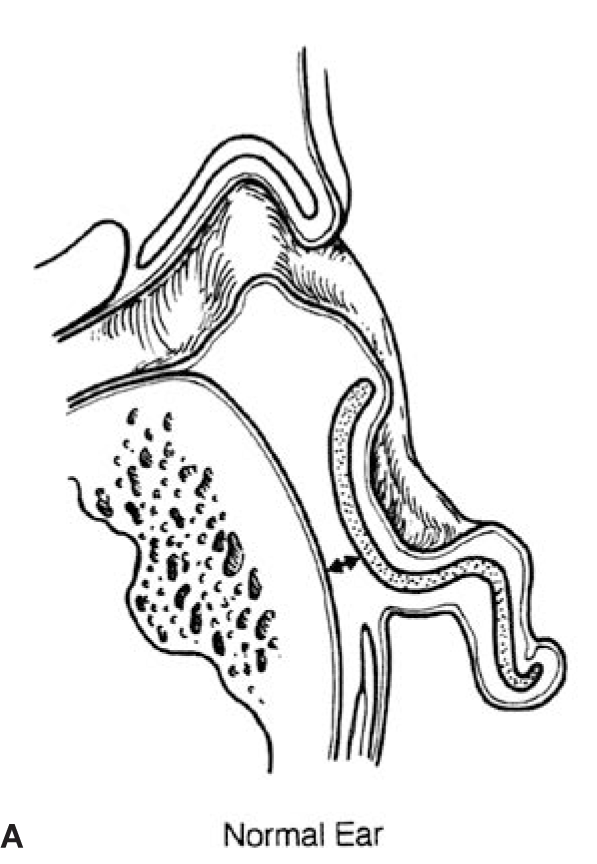

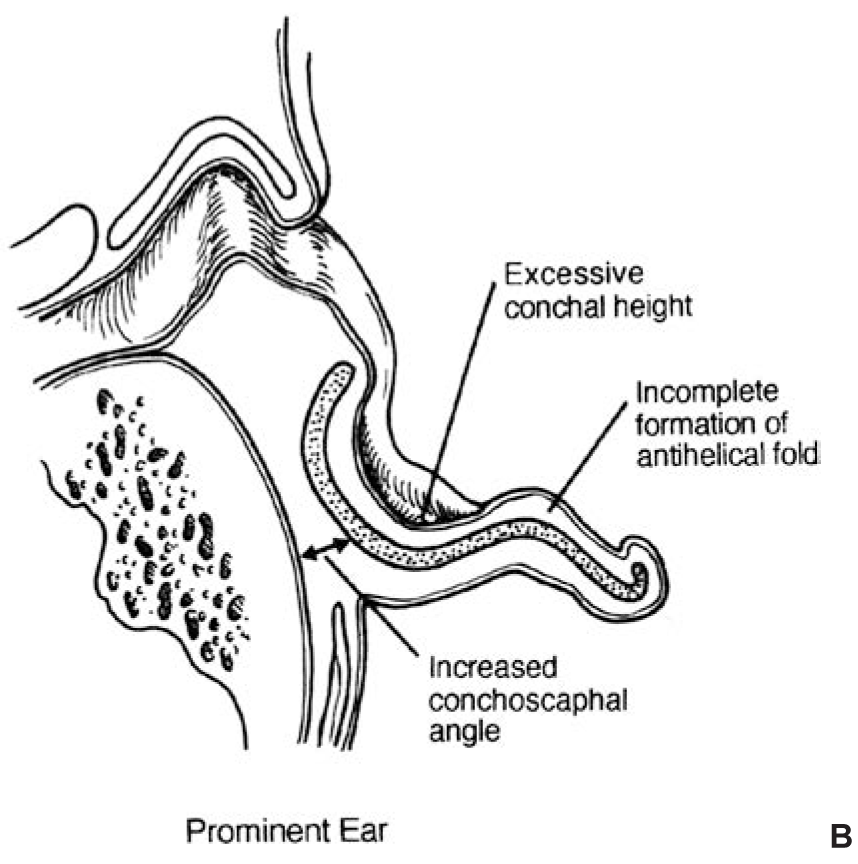

The term prominent ears refers to ears that, regardless of size, “stick out” enough to appear abnormal. When referring to the front surface of the ear, the terms front, lateral surface, and anterior surface are used interchangeably. Similarly, when referring to the back of the auricle, the terms back, medial surface, and posterior surface are used synonymously. The normal external ear is separated by less than 2 cm from, and forms an angle of less than 25° with, the side of the head. Beyond these approximate normal limits, the ear appears prominent when viewed from either the front or the back. While these measurements provide a guideline, aesthetic judgment is more important. In 25 years of dealing with auricular deformities, the author has never measured either the angle with the skull or the distance from the side of the head. To correct prominent ears, the anatomic abnormality is determined (Figure 49.1). The three most common causes of prominent ears are the following and are usually present in combination:

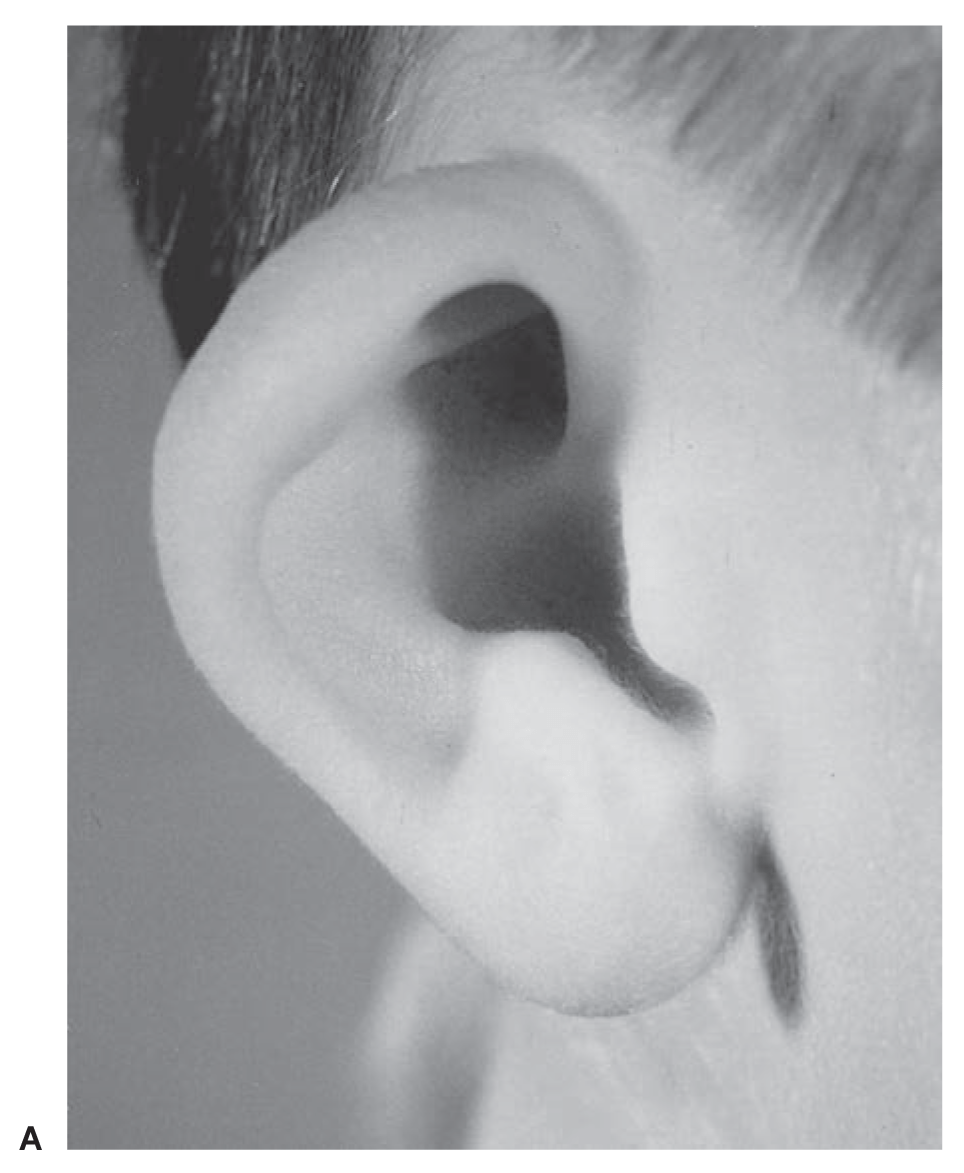

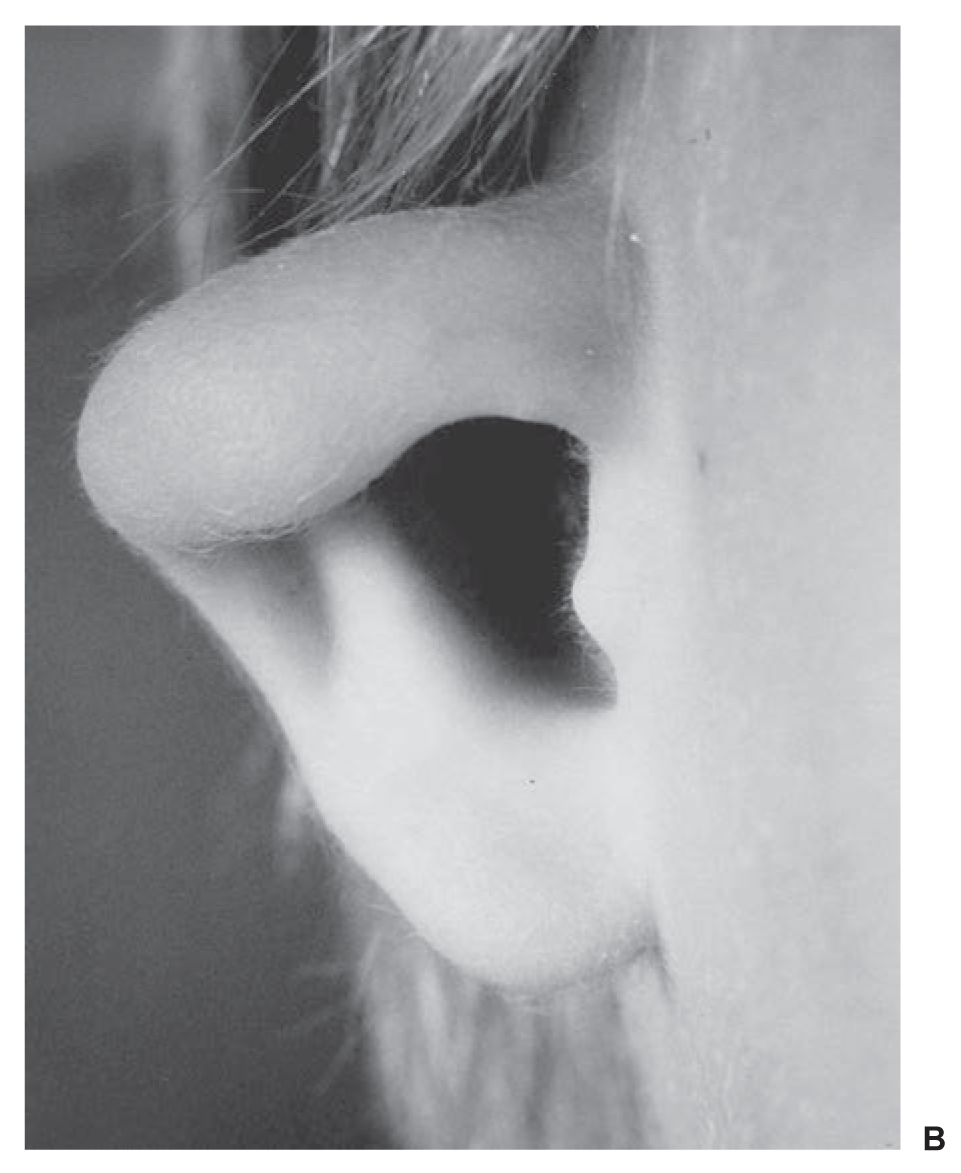

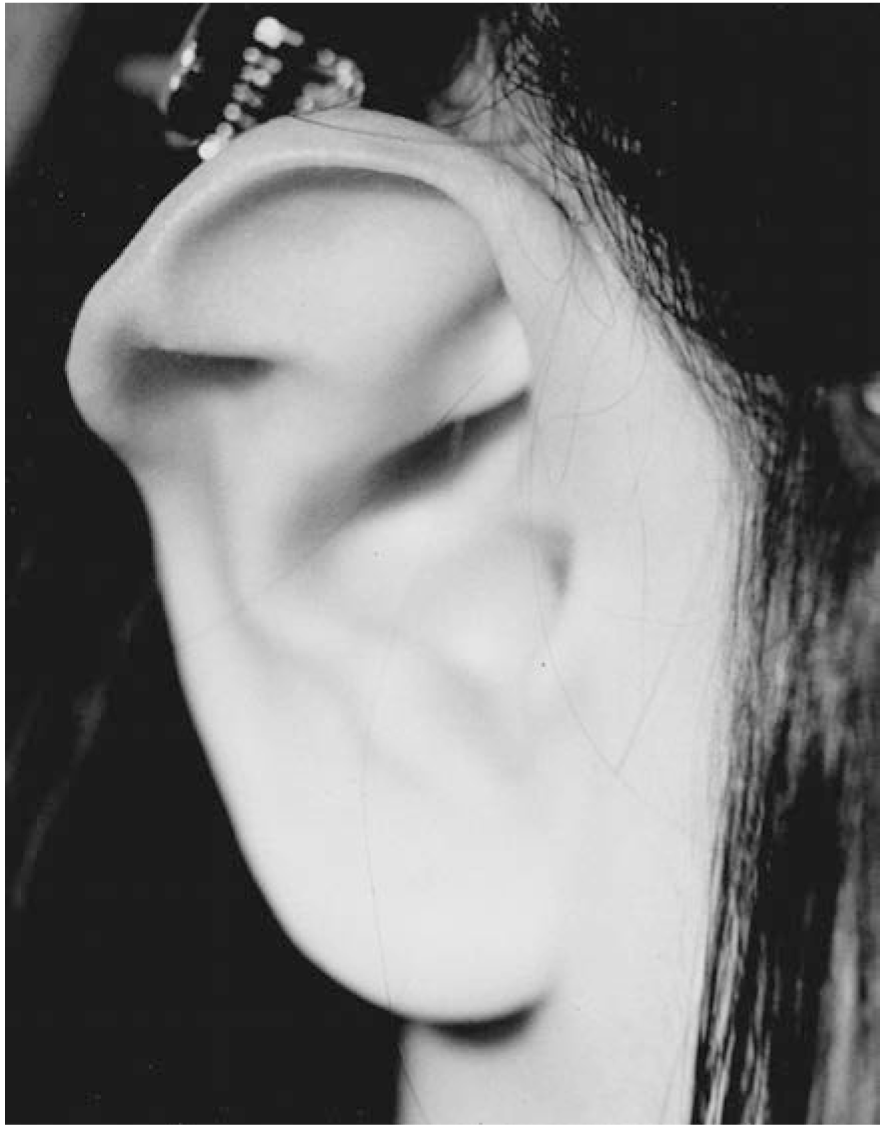

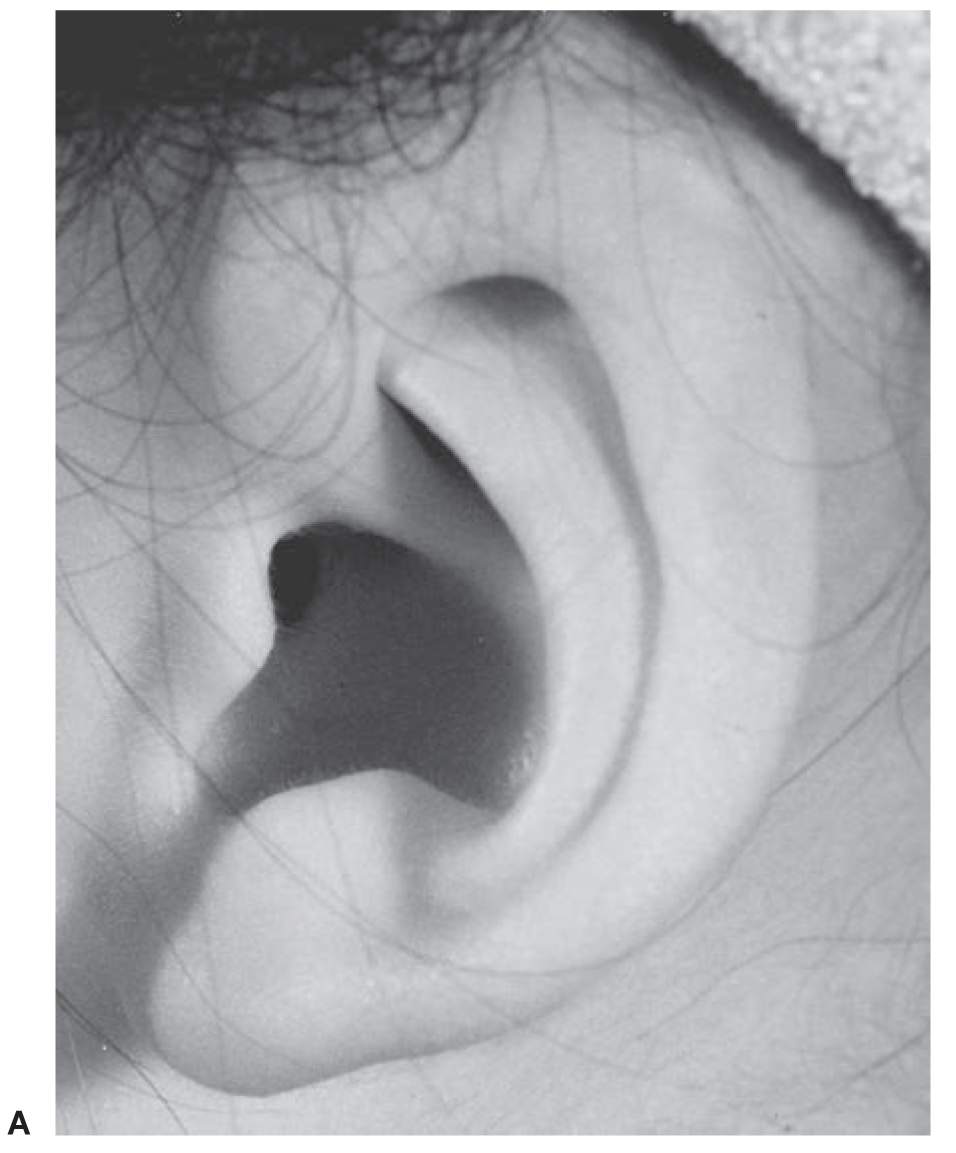

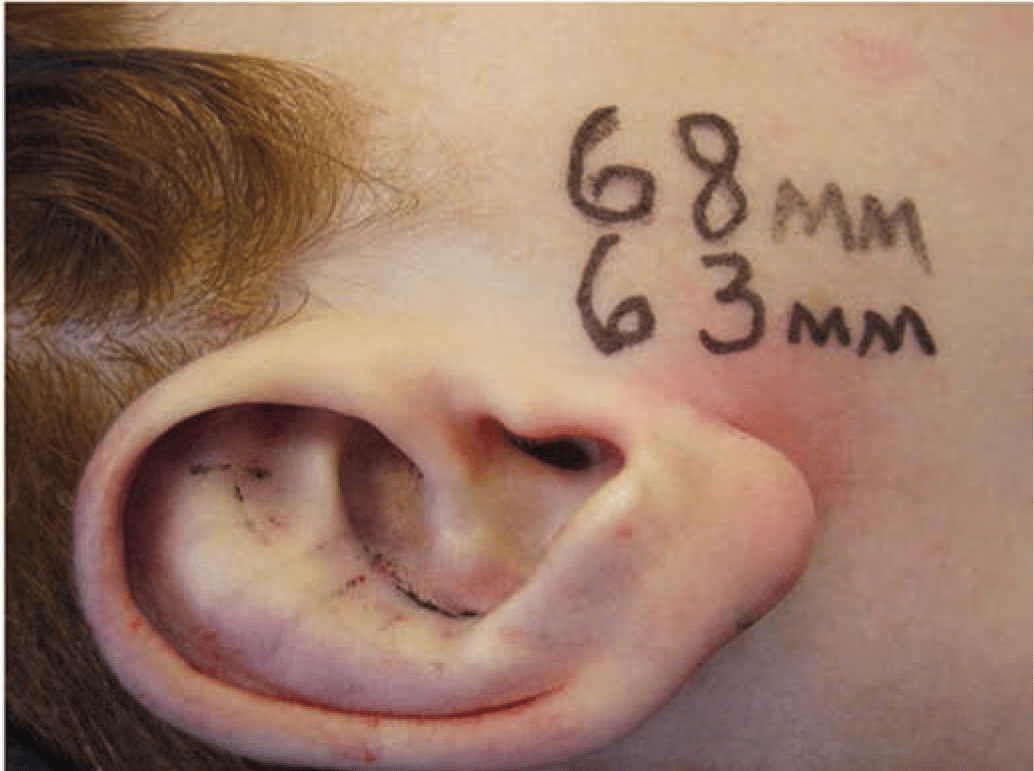

Although most prominent ears are otherwise normal in shape, some prominent ears have additional deformities. The conditions enumerated below are examples of abnormally shaped ears that may also be prominent. The term macrotia refers to excessively large ears that, in addition to being large, may be “prominent.” The average 10-year-old male has ears that are 6 cm in length. Most adults, men and women, have ears in the 6 to 6.5 cm range. In men, ears that are 7 cm or more will look large. In women, ears may look large even if significantly less than 7 cm. Ears with inadequate helical rims or shell ears are those with flat rather than curled helical rims. Constricted ears (Figure 49.2) are abnormally small but tend to appear “prominent” because the circumference of the helical rim is inadequate, causing the auricle to cup forward. The Stahl’s ear deformity (Figure 49.3) consists of a third crus, in addition to the normal crura of the triangular fossa, which traverses the scapha. This may give the ear a “Mr. Spock” pointed appearance in addition to being prominent. Question mark ears earn their name because deficiency of the supralobular region gives the ear the shape of a question mark. The upper portion of the auricle tends to be large and may be prominent as well. Cryptotia (Figure 49.4) describes the auricle in which the upper pole of the helix is buried beneath the temporal skin. Cryptotic ears are not prominent.

The goal of otoplasty is to set back the ears in such a way that the contours appear soft and natural, there is no evidence of surgical intervention, and the setback is harmonious: that is, each portion of the ear appears in appropriate position relative to the rest of the auricle. When examined from the various angles, the corrected auricle should have the following characteristics:

FIGURE 49.1.Comparison of normal and prominent ear anatomy. A. Normal ear. B. Components of the prominent ear. (Reproduced with permission of Charles H. Thorne, MD. Copyright Charles H. Thorne, MD.)

FIGURE 49.2.. Constricted ear. A. Mildly constricted ear. Otoplasty requires increasing the circumference of the helical rim by advancing the crus of the helix into the helical rim (see Figure 49.7). B. Severely constricted ear. This degree of constriction can only be repaired by discarding some of the cartilage and performing an ear reconstruction as in microtia. (Courtesy of David Furnas, MD.)

FIGURE 49.3. Stahl’s ear. Note the third crus that traverses the scapha. (Courtesy of David Furnas, MD.)

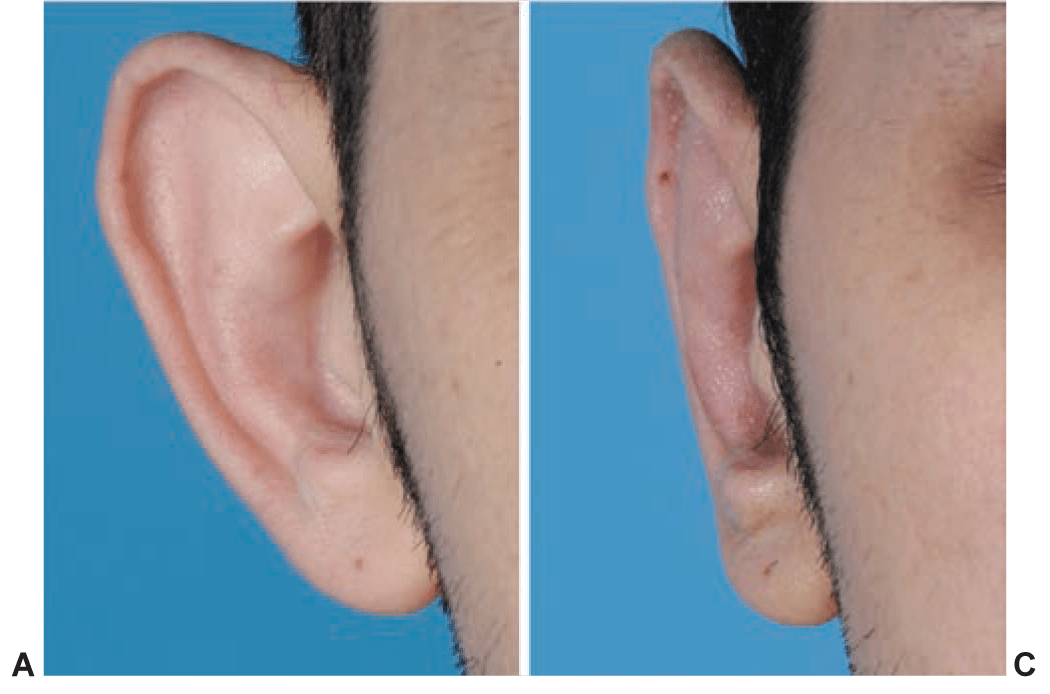

much relative to the upper and lower thirds, the helical urgeryrim will form a “C” when viewed from behind, creating the so-called telephone deformity. Similarly, if the earlobe is insufficiently set back, the rear view will reveal a hockey stick appearance to the helical rim contour.

There is no absolute rule about when otoplasty should be performed. In young children with extremely prominent ears, a reasonable age is approximately 4 years. In cases of macrotia associated with prominence, the author has performed the procedure as early as age 2 years, thinking that any restriction of growth is an advantage. Regardless of the exact age, the procedure requires general anesthesia. In other cases, usually more minor, the parents may choose to wait until the child can participate in the decision. This may allow the procedure to be performed under local anesthesia, although it is a rare child that can tolerate local anesthesia before age 10 years, and many not until they are adults.

Numerous methods have been described for correcting the anatomic abnormalities described above. The techniques that have stood the test of time are the simplest, most reliable, and least likely to cause complications or an “operated” look. The techniques described below are used alone or in combination depending on the anatomic deformity and the choice of the surgeon.

Part V: Aesthetic Surgery

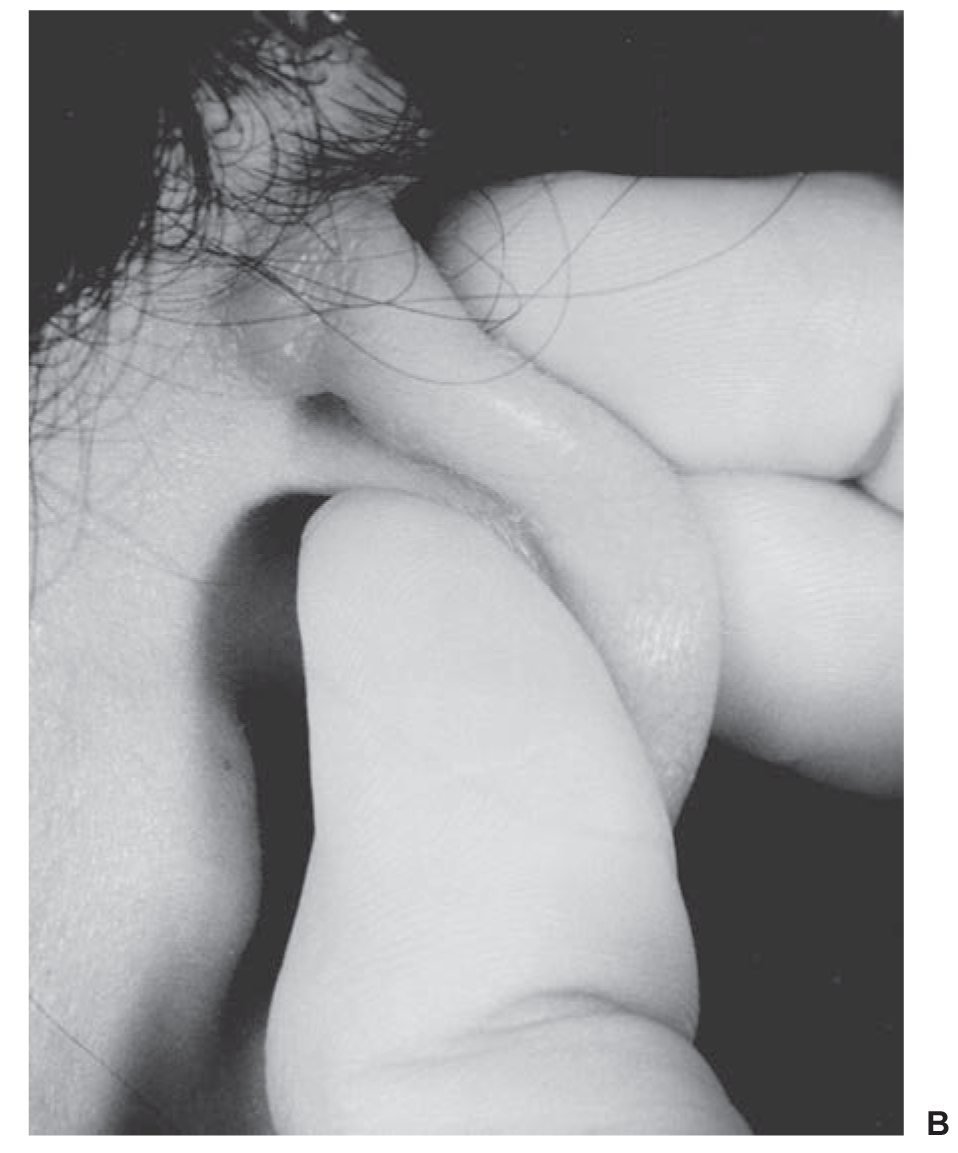

FIGURE 49.4. Cryptotia. A. Patient in whom a relatively normal helical rim is buried in the temporal soft tissues. The upper portion of the auricle can be exposed by outward traction on the ear. B. Outward traction (in a different patient) causes the upper portion of the ear to emerge from its hiding place. (Courtesy of David Furnas, MD.)

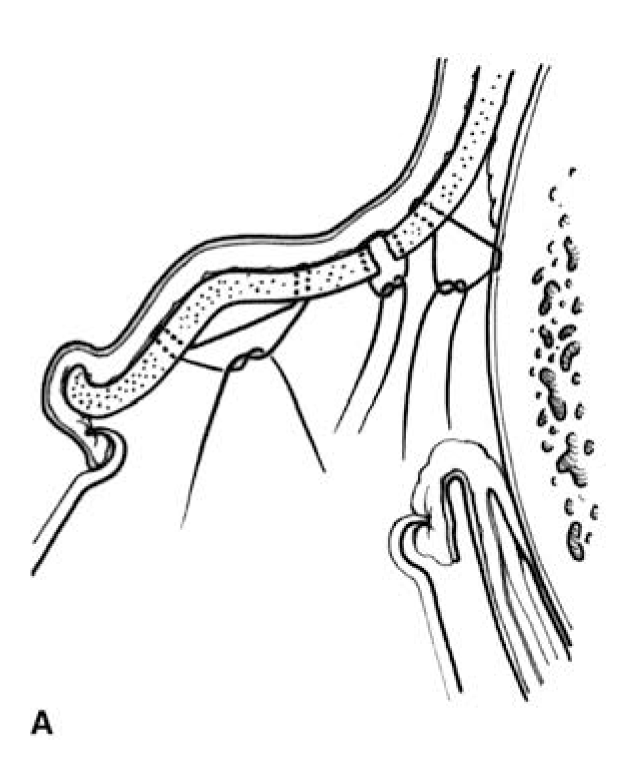

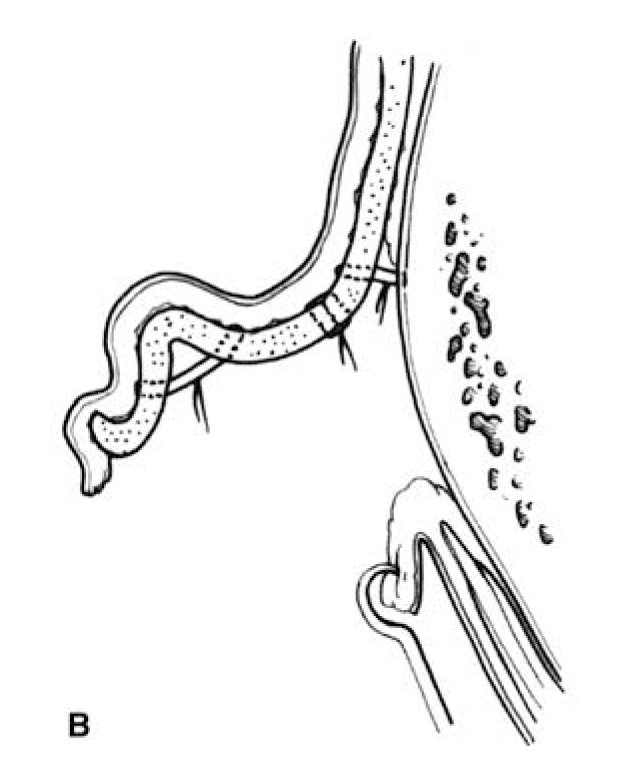

FIGURE 49.5.Otoplasty technique: The combination of a Mustarde scapha-conchal suture, conchal resection with primary closure, and a Furnas conchal-mastoid suture. Note that the conchal closure is at the junction of the floor and posterior wall of the concha. A. Sutures placed. B. Sutures tightened to create the desired contour. C. Same sutures as seen through the retroauricular incision. (Reproduced with permission of Charles H. Thorne, MD. Copyright Charles H. Thorne, MD.)

FIGURE 49.6. . Stenstrom technique. The antihelical fold is scored. The cartilage bends away from the scoring, moving the helical rim closer to the head and increasing the prominence of the antihelix.

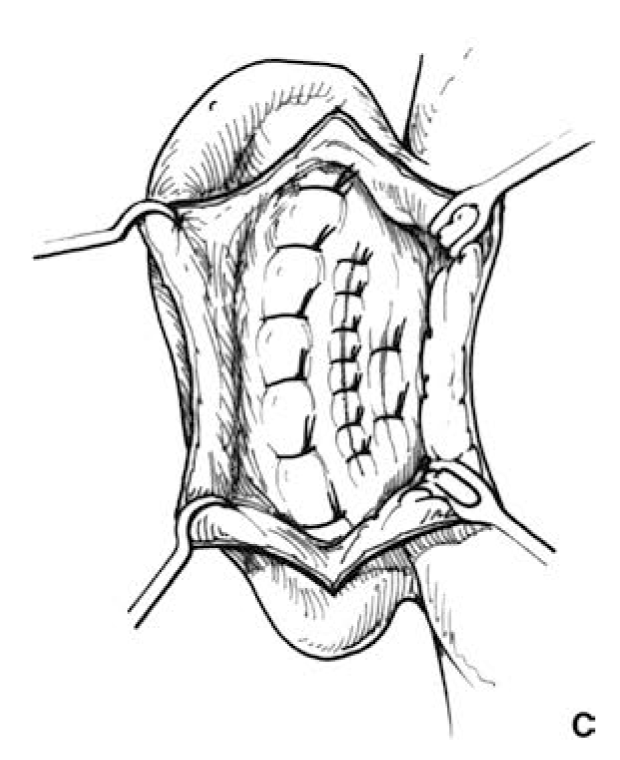

Correction of Earlobe Prominence. Earlobe prominence is not corrected by the above maneuvers. In fact, these maneuvers may increase the prominence of the earlobe, making earlobe repositioning the most difficult and neglected part of the procedure. An auricle that has been repositioned in its upper two thirds but still has a prominent lobule will appear just as abnormal and disharmonious as the original deformity (Figure 49.7). It has been said that suturing the tail of the helical cartilage to the concha will correct earlobe prominence. Unfortunately, the tail of the helix does not extend into the lobule and setting it back does not reliably set back the earlobe. Other authors have described techniques involving skin excision and sutures between the fibrofatty tissue of the lobule and the tissues of the neck. The best technique in the author’s experience is the technique described by Gosain,5 or a variation thereof, in which a small amount of skin is excised on the medial surface of the earlobe. When this defect is closed with sutures, a bite of the undersurface of the concha is taken, which pulls the earlobe toward the head.

Alteration of the Position of the Upper Auricular Pole. Depending on the degree of prominence of the upper third of the ear preoperatively, the antihelical fold creation may be inadequate to correct the position of the helical rim near the root of the helix. In other words, the angle that the helix makes with the temporal scalp is sufficiently large that, even after the Mustarde sutures are placed, an excessive angle exists. An additional mattress suture between the helical rim and the temporal fascia may be required.

The final operative plan for an otoplasty is a combination of surgical maneuvers based in part on the anatomic diagnosis

FIGURE 49.7. Pre- and post-op otoplasty. (AB): Pre-op appearance. (CD): Post-op appearance demonstrating straight helical contour.

of the deformity and in part on the surgeon’s personal preferences.6 This author’s preferred technique involves Mustarde sutures to recreate the antihelix and set back the upper and middle thirds of the ear. The abrasion techniques are unreliable, uncontrollable, and unnecessary and may result in sharp edges or an overdone appearance. It should be noted that the antihelix is not straight; rather it curves forward superiorly, to almost parallel the inferior crus. To create an antihelix of the correct contour, the sutures are not placed parallel to each other but rather placed like spokes of a wheel, with the center of the wheel being the top of the tragus. If the sutures are placed parallel to each other, the antihelix will be excessively straight. In the conchal region, the author most commonly uses both a conchal resection and Furnas conchal-mastoid sutures as shown in Figure 49.5. The combination allows the resection to be small (1 to 2 mm), minimizing iatrogenic deformity. When conchal excision is used alone, a deformity of the posterior wall of the concha may result. When Furnas sutures are used alone, the correction may be inadequate, the patient may have pain, the external auditory canal can be narrowed, and the depth of the retroauricular sulcus is decreased. As mentioned above, earlobe repositioning is the most difficult part of the procedure. The Webster technique of repositioning the helical tail has not been effective in the author’s hands for correction of earlobe prominence. Rather, the Webster technique appears to reposition the ear just above the earlobe, exaggerating the earlobe prominence

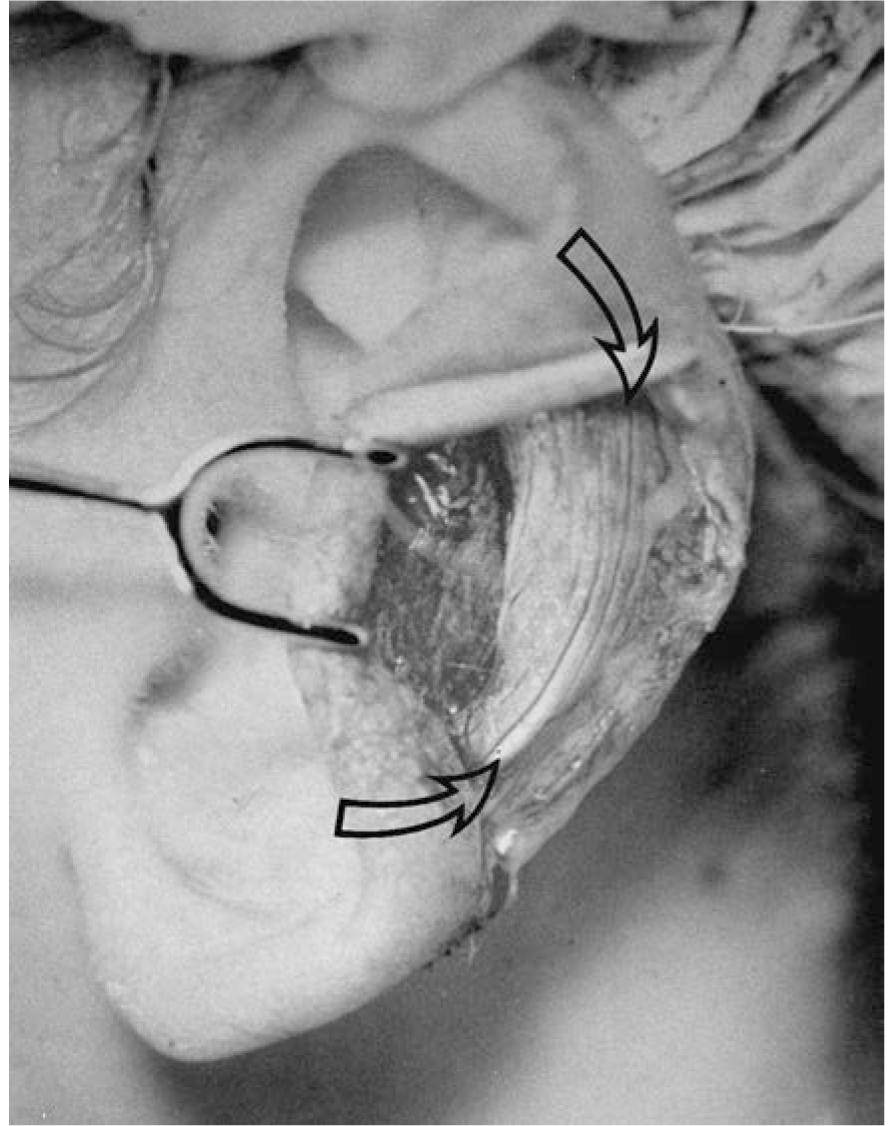

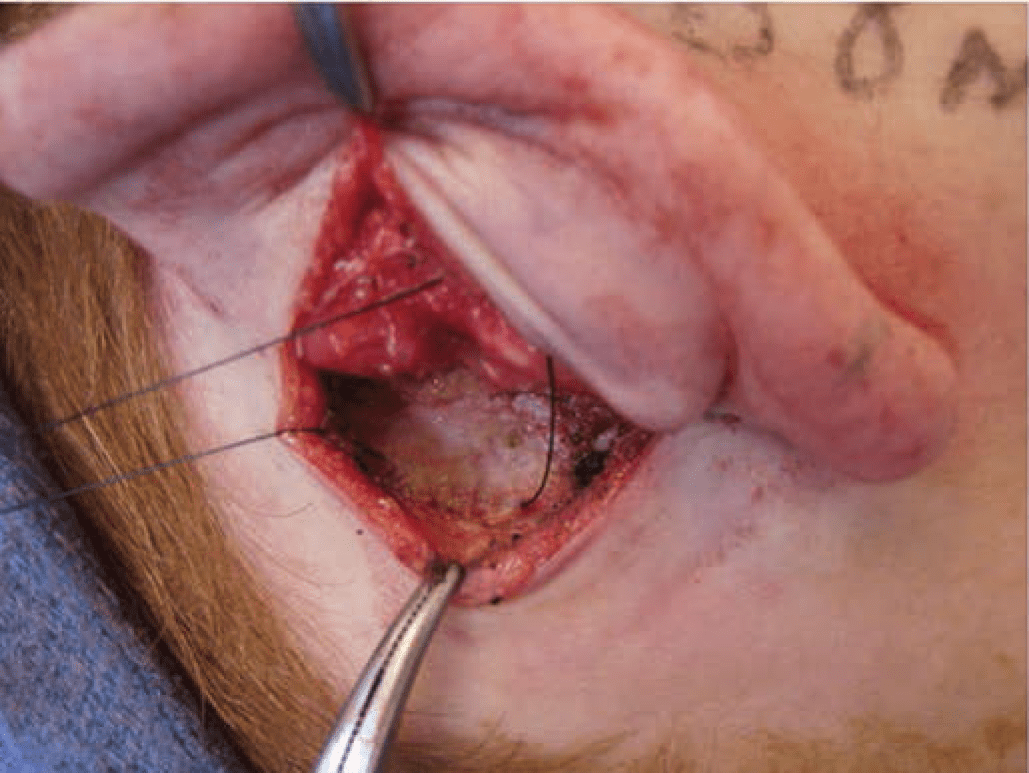

Macrotia. To reduce the size of the ears, an incision is made on the lateral surface of the ear, just inside the helical rim, through the skin and the cartilage, stopping short of the

medial skin (Figure 49.8). A crescent of scapha is removed. A segment of helical rim along with a triangle of medial skin is then excised and closed primarily, so that the helical rim is not redundant relative to the smaller scapha.7,8

Shell Ear. The incision is made as described above for macrotia. The wedge excision of helical rim creates just enough tension not only to allow approximation of the helix but also to create some overhang of the rim.

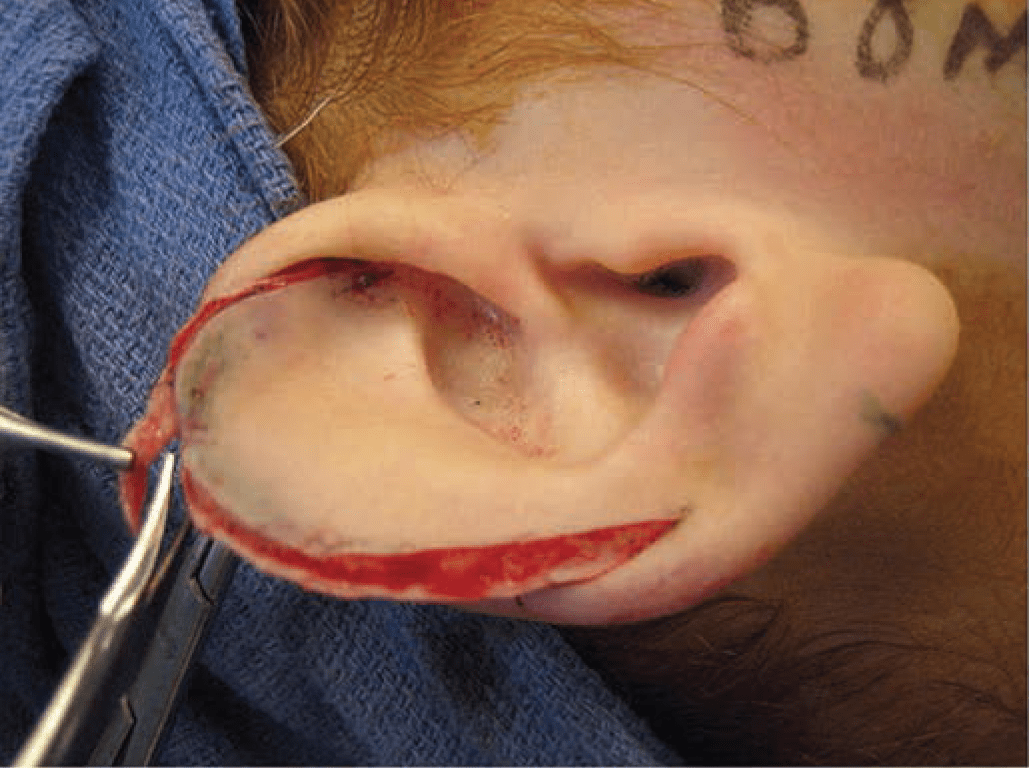

Constricted Ear. A number of complex classifications and surgical procedures have been described for constricted ears, but, from a practical point of view, constricted ears can be divided into three types depending on what procedure is required to repair them. In the mildest cases, the superior helix is folded over, creating the lop ear. Attempts to correct the overhang using mattress sutures will not be successful. Better options include directly trimming the overhanging skin and cartilage (this will leave a slightly short but more normal appearing ear) or resecting the overhanging cartilage only and replacing it with a conchal cartilage graft to increase the height and to improve the shape of the ear. In intermediate cases, the circumference of the helix is inadequate for the rest of the ear, causing it to be cupped forward. These deformities are true to the name constricted ear because that is exactly how the ears look. To improve the appearance, the crus of the helix is advanced out of the concha and into the helical rim, as in the Antia-Buch procedure, and standard otoplasty techniques are used in addition. In severe cases of constricted ear,

the cartilage is discarded and a complete auricular reconstruction performed as in microtia (Chapter 27).

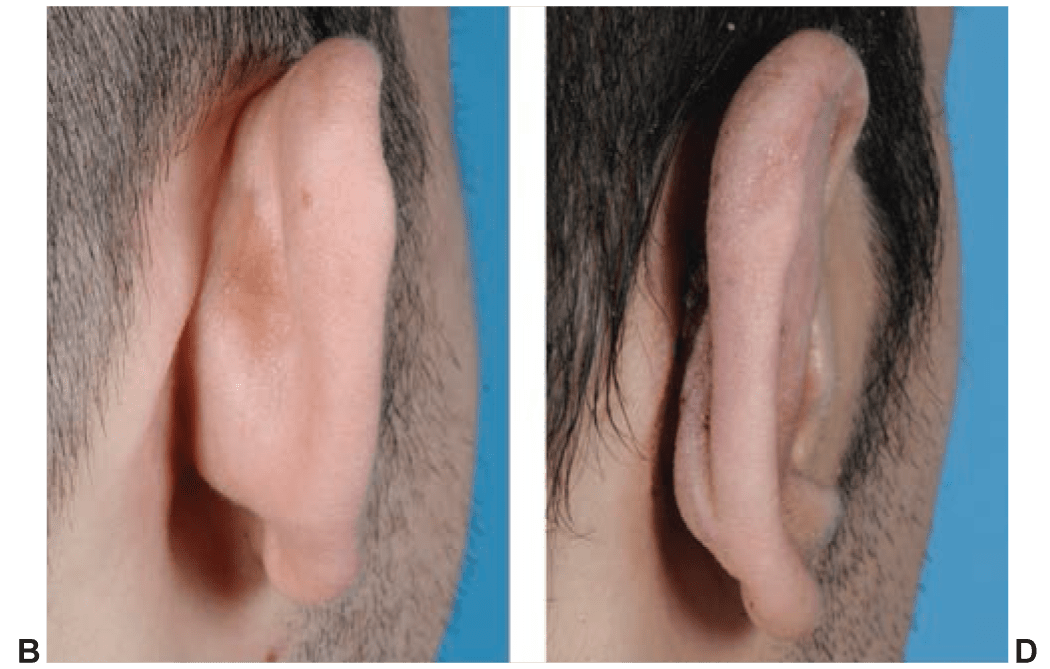

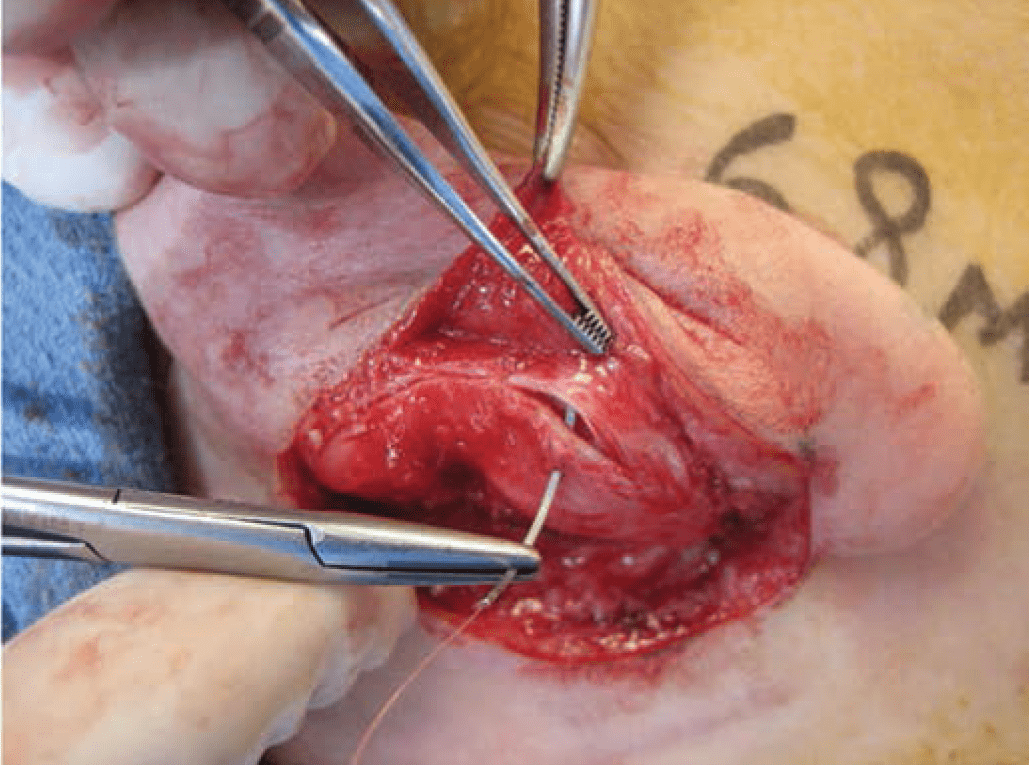

Stahl Ear. Various techniques have been described to excise the extra crus. This author prefers the technique described by Kaplan and Hudson.9 An incision is made inside the helical rim, the lateral skin is carefully dissected off the cartilage, the extra crus is excised, and the cartilage defect is closed primarily. The excised cartilage can be used as an onlay graft to reconstruct the superior crus of the triangular fossa (Figure 49.9).

Cryptotia. The superior aspect of the auricular cartilage is pulled out from under the scalp, an incision is made around the now-visible helical rim, and the medial surface of the freed cartilage is resurfaced with a graft or flap. In some cases, the buried cartilage is quite normal, and in other cases, it is markedly abnormal and requires modification.

Question Mark Ear. The supralobular deficiency is variable. Repair requires a cartilage graft. In milder cases, this can be taken from the concha and resurfaced with a V-Y advancement of the medial skin. In more severe cases, a rib cartilage graft is required and a standard two-stage reconstruction is performed, as one would perform for a significant posttraumatic defect (Chapter 27).10,11 The deformity is often associated with excess tissue in the upper third of the ear requiring reduction. In the severe cases, the entire ear is reconstructed as in microtia.

FIGURE 49.8. Technique for reduction otoplasty. (With permission from Thorne CH, Wilkes G. Otoplasty, ear deformities and ear reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):701e, Figure 2.)

FIGURE 49.9. Technique for repair of Stahl’s ear. (With permission from Thorne CH, Wilkes G. Otoplasty, ear deformities and ear reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):701e, Figure 3.)

A bulky, noncompressive dressing is placed for a day or two. Excessive pressure from the dressing will cause pain, increase swelling, and may lead to abrasion or even necrosis of auricular skin. When the dressing is removed, the patient wears a loose headband at night only for 6 weeks. Again, the headband should only be tight enough that it does not fall off. The purpose is to prevent the corrected ear from being pulled forward when the patient rolls over in bed. A tight headband can erode the lateral surface of the ear, creating an open wound.

During the early weeks of infancy, the auricular cartilage has unusual plasticity, attributed to circulating maternal estrogens. During this privileged period, prominent ears and related deformities can be corrected permanently by molding the ears into the correct shape with tape and soft dental compound.12,13 The splints and tape are replaced regularly, and the skin is checked compulsively for erosion. The process is continued for several months or until there is no further improvement in auricular contour. This ability to mold cartilage is currently being exploited in presurgical molding of the cleft nasal deformity (Chapter 23). It is not clear how long cartilage retains this “moldability” and therefore it is not clear when infants are too old to have this technique attempted.

Hematomas are one of the few early complications of otoplasty. Excessive pain or bleeding necessitates immediate removal of the dressing to rule out and, if necessary, evacuate a hematoma

Cellulitis is rare after otoplasty but is treated aggressively with intravenous antibiotics in an attempt to avoid chondritis. The latter may require debridement and leave the ear permanently disfigured.

By far the most common complication of otoplasty in the author’s experience is related to suture extrusion in the retroauricular sulcus. Such sutures are easily removed but may be associated with unattractive and/or painful granulomas. The use of absorbable sutures might eliminate this complication but the author has not had the courage to abandon permanent sutures. The author prefers monofilament sutures that are less likely to form pustules or granulomas when protruding through the skin. On the other hand, the monofilament sutures require more knots and may be more likely to protrude through the skin in the first place.

The most common significant complication of otoplasty is overcorrection. Attention to the principles outlined above will minimize overcorrection and the creation of unnatural contours

The author’s personal thoughts about otoplasty are as follows6: